https://ilmin.org/ima_on/2024_ima-critics_exhibition-critics

As a part of IMA Critics, the critical research program of Ilmin Art Museun(Seoul, Korea), I authored a review of Cha Jaemin’s solo exhibition, Stories of Visible Spectrum. Below is an English translation.

Among the Scattering Bodies

Stories of Visible Spectrum (Ilmin Museum of Art, 8.30–11.17, 2024)

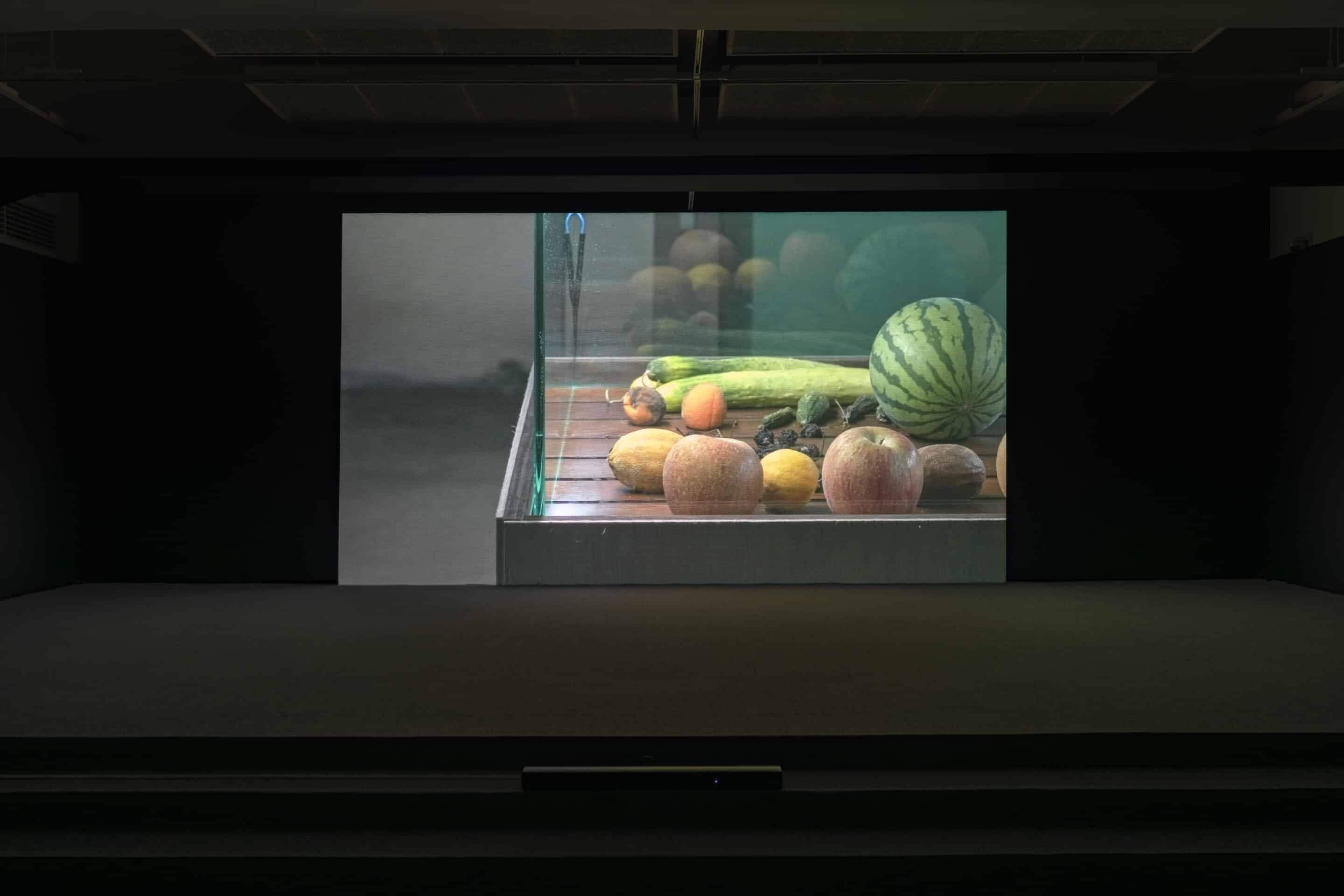

Broken into little pieces, a flock of lights drifts through an empty house like butterflies. Exhibition stands covered with glass are placed in front of a broad window, displaying fruits, bread, mushrooms are gradually rotting. Against this backdrop, a voice recites brief correspondences. Cha Jaemin’s solo exhibition, Stories of Visible Spectrum (Ilmin Museum of Art, 8.30–11.17, 2024) centers on a single-channel essay film, Photosynthesizing Dead in Warehouse (2024), led by this voice and complemented by related drawings and a sculpture. Presenting the decomposition of groceries, Photosynthesizing Dead in Warehouse lets us hear the process of research about kusōzu (九相図, Nine Stages of Decay)—a Japanese Buddhist painting tradition depicting nine stages of a decaying corpse. Cha introduces this work as “a neo-kusōzu” throwing “questions about death,” examining two activities of “looking at things as they are” and “making up stories in an attempt to make sense of them.”1 These dual acts—observation through sensation and reflection through symbolic activities like art and religion—are embodied in the imagery of rotting groceries and the story of kusōzu, inviting the audience to observe and reflect what is seen and heard, connecting the two elements.

This film is extends Cha’s previous works, which explore the tension between society and individuals, technology and life, and language and reality, both in its form and content. Cha’s moving images often juxtaposes two stories. For instance, Sound Garden (2019) intertwines the story of saplings “trained” to survive as street trees in urban environments with the narration of psychological counselors describing their work. This layering suggests that counseling involves both healing patients and reintegrating them as functional components of a capitalist society. Similarly, On Guard (2018) examines the overlap between caring and guarding, highlighting the labor of a safety guard and a care-worker. In Sleep Walker (2009), Cha juxtaposes the plight of merchants displaced by redevelopment with the narrative of the children’s story Heidi, where the protagonist experiences sleepwalking caused by nostalgia, illuminating the struggles of those unable to find their place in large cities. Photosynthesizing Dead in Warehouse continues this approach, shedding lights on the parallels and distinctions between its imagery and narration.

The new work, which portrays the abstract reality of death and extinction, resonates with Four Variations: Recitation, Constellation, Silence, and Shadow (2023), an earlier piece that sought “to sense the gap created by the distance between language and reality in the most silence.”2 The question of the world’s residue—what cannot be defined or confined by language—confronts death, the “indecipherable”3 which cannot be reached with any language. In this work, Cha focuses on the painting of decomposing corpse transitioning into inorganic matter, highlighting the molds tearing apart the bodies of groceries. This review will follow the structure of the work, which juxtaposes the dual activities of observing and reflecting on death through video and audio elements, and will explore how the exhibition probes the gap between them.

Observation and Reflection

In Photosynthesizing Dead in Warehouse, the audience sees various fruits, vegetables, mushrooms, and bread festering and being overtaken by fungus. While reminiscent of Still Life (2001) by British artist Sam Taylor-Wood, Cha’s work captures decay from distinct close-up perspectives, rather than composing a single picture like a classical still life. Furthermore, instead of employing a smooth timelapse from a fixed position, the film uses numerous shots taken from slightly different angles and at different times. The editing emphasizes these disjointed transitions, drawing attention to the shifting standpoints of observing the decaying objects.

From one shot to the next, black spots appear on the surface of the bread, while pears and apricots, initially intact without cracks, shrink and become covered in wrinkles. A cucumber ulcerates, whereas a watermelon, protected by its thick rind, maintains its shape for a long period. In the middle phase, however, everything is overtaken by mycelia, blending into a single mass as individuality dissolves. Only scattered fibers and stains remain by the end. As things that used to grow as a part of plant are decomposed under the hypha, the living intervene—the rotting liquid attracts flies, and swarms of white maggots crawl in and out of glass. Young or old visitors come day and night, peer into the exhibition stands, and leave. The camera, observing the decay, seems to indicate the gaze of the people in the video.

Meanwhile, the narration is composed with correspondences from the fictional researcher Shimura Hikaru to Cha and emails from Shimura to the temples owning kusōzu. Rather than presenting a documentary that synthesizes researched materials into a focused narrative, this film adopts the form of an essay, revealing the fragmented and distracted process preceding such synthesis. As a result, these correspondences provide limited information about kusōzu during the film’s 30-minute runtime. They neither delve into the historical context exploring kusōzu as a unique salience nor mention ‘Reflections on Repulsiveness (Patikulamanasikara)‘, a foundational Buddhist meditation practice underlying kusōzu. A brief question regarding why kusōzu exclusively depicts female bodies is raised, but it is not integrated into the overall flow.4 Instead of engaging deeply with academic knowledge, the narrator offers loose fragments of thought on life and creation, reality and image, as they flash across his mind. The use of correspondence, a medium often associated with casual conversation, blurs the line between research and the concreteness of everyday life.

Between Reality and Story

Since, or even before, the dawn of civilization, humanity has sought to built order of meaning on the incomprehensible infinity of the world by defining and connecting boundaries of things through symbols, such as language. However, the event of death incapacitates this symbolic order—these “stories”—relentlessly. Each death is innumerably individual, specific, and unique, yet stories, by their very nature, fail to encompass the countless faces of death due to their inherent finitude. Those who confront death witness the collapse of the fence of determination that has safely encircled us until that moment. They struggle to mend the hole of language, to shroud the death with meaning, and to incorporate it into the realm of the comprehensible. Yet the reality, unable to be confined with finite language, and the indeterminable nothingness and emptiness inevitably pour through the crack.

How does kusōzu, one of the countless “stories” around death, address this hole? In it, a being that once animated life with a unique soul, thought, and speech, falls into the domain of insects and mycelia. Kusōzu is grounded in ‘Reflections on Repulsiveness’, a Buddhist meditation practice aimed at overcoming sensual desire and recognizing the impermanence (anicca) of life by confronting the impurity and loathsomeness of the body. This includes ‘Observation of a Corpse‘ rather than a living body, as expressed in a Buddhist scripture: “O bhikkhus, if a bhikkhu, in whatever way, sees a body, thrown in the charnel ground and reduced to a skeleton together with (some) flesh and blood held in by the tendons, he thinks of his own body thus: ‘This body of mine, too, is of the same nature as that body, is going to be like that body, and has not got past the condition of becoming like that body.’”5 This involves realizing that the body is merely a part of the material cycle of arising and dissolving, free from the illusion of ownership, that there is no me, nor mine, nor anyone, nor anyone’s, and therefore gaining awareness of impermanence—that everything comes into being and passes away without a lasting essence.6

The custom of burying corpses underground was uncommon in medieval Japan when kusōzu was painted. At that time, most corpses were exposed to sunlight, rain and wind, instead of being burned into ashes or hidden under the earth.7 Death, which swallowed the living, “photosynthesized” under the same light as the alive. The convention of leaving corpses on the ground, such as sky burials, existed in other cultures but was mostly eradicated or restricted during modernization. Today, even images of decomposing corpses are treated as taboo, separated from the space of life.

Rather than shocking the audience with tabooed imagery, Photosynthesizing Dead moderately implies the decomposition that occurs in a body—a structure of matter—through the sight of decaying groceries—edible matter that could form human flesh and blood. Spoiled, moldy food is not an unfamiliar sight, but it is typically discarded immediately and expelled from everyday spaces. This work reveals the process in its entirety, confronting what is usually exorcised and concealed within the normative order of life—health and hygiene. The decay “photosynthesizes” under sunlight streaming through the window, rather than in the darkness of a dump, gazing at the audience beyond the camera and glass, with “visible spectrum” reflected on its body.8 While the audience may feel disgusted, this gaze releases the material which can be synthesized as a new story. As Jane Bennett’s vital materialism, cited by Cha in a correspondence, suggests: “The body is made of matter and that matter has the ability to organize and act itself,” and “death doesn’t mean that existence disappears; it changes into a different form.”9

A series of gouache drawings—Study for ‘Photosynthesizing Dead in Warehouse’ 1, 2 (2024), Still Life Study Series (2024), Scene Study for ‘Photosynthesizing Dead in Warehouse’ Series (2024) and Kyoto Trip Series (2024)—along with the bronze sculpture Dummy Flock (2024), also depict the decomposition of groceries featured in the video. In these works, Cha engages in a meditation of kusōzu, representing decaying bodies through her own bodily gestures. She gropes the movement of mycelium with her hands, which overgrows in all directions, disrupts the outlines of the individuals, and binds them into nameless masses. The traces of her hands emerge as a nonfigurative, informal landscape to the audience.

Perception before Thought

The task of the exhibition—to contemplate “the act of seeing directly without any filter”10 and “looking at things as they are”11 beyond the boundary of thought drawn by stories—parallels the aim of phenomenology, which seeks to uncover the immediate relationship we have with the world. Phenomenology tries to “give a direct description of our experience as it is”.12 According to phenomenologists like Maurice Merleau-Ponty, the world is not inherent within consciousness that determines and judges things but exist prior to such judgment. We are beings who live with a body in the world before we are beings who construct the world through consciousness. Seeing and feeling the world as being-in-the-world—the activity of perception—forms the foundation of all ideas, all “stories”.13

Because it is done through a body, perception is always made in a specific spatiotemporal position, rather than a static, transcendental viewpoint. We are linked to the system of things by a perceiving body, and things are given to us as an infinite totality of countless gazes. The meaning of object does not show up at once as single and ultimate by thinking and reasoning, but gradually appears among crossing gazes.14 In Photosynthesizing Dead in Warehouse, the audience finds out the changing faces of the decay by following the close or distant gazes of the camera, instead of overlooking from a motionless, neutral standpoint. The black and white fruiting body, which constantly extends itself into the space and time, gazes us, while acting with the order and principle that we cannot fully count.15 The meeting gaze seems to talk to us: ”This body of mine, too, is of the same nature as that body, is going to be like that body, and has not got past the condition of becoming like that body.”

From the Real to the Story again

Meanwhile, the “story” presented through language by the narration often restricts the meaning conceived by the video. While establishing the narrator as a fictional character may aim to process the content of the correspondences, the scattered fragments of information and thought fail to coalesce into a unified narrative. In addition, whereas the Observation of a Corpse involves confronting death and decay, which attacks the order of the Symbolic from outside its boundaries, the narration remains within the safety of humane language in this order, deflecting the purpose of the Reflection on Repulsiveness—to attain the most abstract and liberating wisdom through the most vulgar and detestable material. Just as the people in the video maintain a safe distance from the decomposed matter through the glass, the narration hovers over the veil of language, rather than delving into the hole of language.

Nevertheless, Stories of Visible Spectrum reveals that everyday life is in a constant progress of searching for new stories. The video begins with a restless flock of light and ends with a letter arranging the artist’s visit to Kyoto, accompanied by the sound of raindrops filling the space. Just as the sound and humidity permeate the interior, death seeps into life while matter transforms itself. The audience does not know what the artist and Shimura would see in kusōzu, as the work refrains from offering a closed story. Instead, it gives the audience a practice of the Reflection on Repulsiveness, who may search for the image of kusōzu afterward, planting the seed of a new story they might uncover in the decay of groceries in daily life. The decomposed, presented in the form of an exhibition, suggests that museums are places for contemplating the boundary between reality and language. A Buddhist scripture preaches the impact of the Observation of a Corpse: “And he lives independent, and clings to naught in the world. Thus, also, O bhikkhus, a bhikkhu lives contemplating the body in the body.“16 As we gaze upon the decaying body, the body gazes back at us, remaining with us in the space between reality and language, as a composition of materials that will one day exchange places with one another.

- Jaemin Cha, “Photosynthesizing Dead in Warehouse,” https://jeamincha.info/works/photosynthesizing-dead-in-warehouse. ↩︎

- Jaemin Cha, “Four Variations: Recitation, Constellation, Silence, and Shade,” https://jeamincha.info/works/p. ↩︎

- In the narration of Photosynthesizing Dead in Warehouse. ↩︎

- The work explains only that a woman depicted in kusōzu was praised for granting men enlightenment. However, in kusōzu, painting a female corpse originally aimed to eliminate sexual desire toward the female body for male practitioners. Fusae Kanda, “Behind the Sensationalism: Images of a Decaying Corpse in Japanese Buddhist Art,” The Art Bulletin, vol. 98 (2005): 24–29. This custom of kusōzu has been interpreted as a visual sign of misogyny in Japanese Buddhist thought. Conversely, Gail Chin argues that the female body must be considered capable of presenting truth for it to serve as a medium for enlightenment. Gail Chin, “The Gender of Buddhist Truth: The Female Corpse in a Group of Japanese Paintings,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, vol. 25, no. 3–4 (1998): 277–317. ↩︎

- Soma Thera, The Way of Mindfulness The Satipatthana Sutta and Its Commentary, https://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/soma/wayof.html. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Fusae Kanda,“Behind the Sensationalism: Images of a Decaying Corpse in Japanese Buddhist Art,” 25. ↩︎

- Cha named the exhibition in English as Stories of Visible Spectrum, rather than using a literal translation of the Korean title, “Stories of Light (빛 이야기)”. ↩︎

- Jaemin Cha, “The First Correspondence”, Almost One (aurumbooks, 2024), 177–178, http://almost-one.com/. ↩︎

- In the narration of Photosynthesizing Dead in Warehouse. ↩︎

- Jaemin Cha, “Photosynthesizing Dead in Warehouse,” https://jeamincha.info/works/photosynthesizing-dead-in-warehouse. ↩︎

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, trans. Colin Smith (Rutledge, 2005), vii. ↩︎

- Ibid., vii–xxiv. ↩︎

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “The Primacy of Perception and Its Philosophical Consequences”, trans. James M. Edie, in The Primacy of Perception: And Other Essays on Phenomenological Psychology, the Philosophy of Art, History and Politics (Northwestern University Press, 1964), 12–42. ↩︎

- Merleau-Ponty dismissed the early modern dichotomy of subject and object, arguing that perception arises not unilaterally but from a reciprocal relationship: the I as seeing things and the I as seen by things. Influenced by this perspective, Lacan proposed the theory of the gaze, suggesting that when the subject gazes at things, things also gaze back at the subject. He illustrated this concept with his experience of light reflected off a sardine can floating on the sea, which suddenly flashed at him. Lacan refers to the imagery of visual art as a “screen,” claiming it shields us from the threatening gaze of the Real. See Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible, Followed by Working Notes, trans. Alphonso Lingis (Northwestern University Press, 1968); Jaques Lacan, The Seminar, Book XI, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. Alan Sheridan (W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 1977). For related discussion in contemporary art, see Hal Foster, The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century (MIT Press, 1996). Meanwhile, Bennett focuses on the active agency of matter, traditionally regarded as inert objects. She argues that this non-human “actant” possess the capacity to produce effects on human and other bodies. Bennett observes that things function “as vivid entities not entirely reducible to the contexts in which (human) subjects set them, never entirely exhausted by their semiotics.” Jane Bennet, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Duke University Press, 2010), 5. ↩︎

- Soma Thera, The Way of Mindfulness The Satipatthana Sutta and Its Commentary. ↩︎